A Beginner's Guide to Git

git is

currently one of the most popular

DVCS (Distributed Version Control Systems)

in use. Created by

Linus Torvalds, known as the "father of Linux," in 2005,

git not only offers powerful features but also embodies a

spirit of resilience and independence. Its history reflects the humor

and defiance of master developers and open-source advocates, something

that has always impressed me deeply.

Below is a quote from the Chinese version of Wikipedia that describes the backstory (original source here; English version here):

In 2002, Linus Torvalds decided to use BitKeeper as the main version control system for maintaining Linux kernel code. Since BitKeeper was proprietary software, this decision was long criticized within the community. Particularly, Richard Stallman and members of the Free Software Foundation argued that an open-source tool should be used for the Linux kernel's version control. Linus considered using existing solutions like Monotone, but these tools had various issues, particularly with performance. Other systems like CVS were dismissed by Linus for their architecture.

In 2005, Andrew Tridgell wrote a simple program that could connect to BitKeeper repositories. Larry McVoy, the owner of BitKeeper, believed that Tridgell had reverse-engineered the protocol used by BitKeeper and decided to withdraw the free usage rights of BitKeeper. Negotiations between the Linux kernel development team and BitMover failed to resolve the differences. As a result, Linus decided to create his own version control system to replace BitKeeper, and in just ten days, he developed the first version of git.

git has since become more than just a version control

tool for programmers; it's widely adopted and now serves as an

essential collaboration tool for many projects. Whether it's gathering

data or writing articles, git offers a highly valuable

skill for both work and daily life.

This article follows my usual tutorial style, aiming to provide a quick introduction. For those who want to dive deeper, I highly recommend referring to the official documentation. Here are some useful resources:

Popular git hosting platforms:

Now, let's dive into the content. I hope this guide will be helpful, and feel free to email me if you spot any errors.

Table of Contents

- Step 1: Creating or Cloning a Repository

- Step 2: Setting Your Identity

- Step 3: Recording Changes

- Step 4: Viewing History and Changes

- Step 5: Reverting Changes

- Step 6: Managing Remote Repositories

- Conclusion

Step 1: Creating or Cloning a Repository

Before using git, we first need to create or clone a

git repository (hereinafter referred to as

repo). There are two ways to set up a repo:

-

Create a local repository: Start from scratch by

initializing a new

repolocally. -

Clone an existing repository: Clone an existing

repofrom a remote service to your local machine.

Creating a Local Repository

Creating a repo locally is straightforward. First,

navigate to the directory where you want to initialize the

repo:

$ cd /my/git/repo

Then, use the git init command to initialize the

repository:

$ git init

After running this command, a hidden .git directory will

be created within the specified folder. This

.git directory contains all the internal data and version

control information that git needs. Generally, you do not

need to manually modify anything inside .git, as

git commands will handle everything for you.

Cloning an Existing Repository

If you want to use an already existing repo, you can

clone it from a remote service. First, navigate to the local directory

where you want the cloned repository to reside, then execute:

$ git clone <url>

This command will download all the contents of the remote

repo, including its full commit history, and will

automatically set up the remote reference (which we will

discuss later).

With your repo set up, you are now ready to explore

git and begin your version control journey!

Step 2: Setting Your Identity

Before using git, the first thing we need to do is

configure our personal identity, specifically our

name and email address. This

information is essential for version control, as it allows

collaborators to identify who made each commit. It also ensures that

your contributions are properly attributed, which can be particularly

rewarding when working on open-source projects.

Beyond identification, setting up your personal identity correctly can

prevent future issues. In large projects or shared repositories,

modifying user information retroactively can be cumbersome.

Personally, I learned this the hard way. When I first started using

git, I was unaware of this setting, and all my commits

were recorded under my computer's default username. Seeing that in my

git log was frustrating, to say the least. To avoid such

issues, it is best to set up your identity correctly from the start.

To configure your global identity (applicable across all

git repositories), use the following commands:

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

$ git config --global user.email "your-email@example.com"

If you need to override these settings for a specific

repo without affecting the global configuration, you can

use the --local option instead:

$ git config --local user.name "Your Name"

$ git config --local user.email "your-email@example.com"

To explore additional configuration options, refer to the manual:

$ man git config

You can also verify your current configuration by running:

$ git config -l

Once your identity is correctly set up, you are ready to move forward

and start using git effectively!

Step 3: Recording Changes

Now, we are diving into the core functionality of git:

tracking and recording changes. As a version control system (VCS),

git's primary purpose is to monitor file modifications

efficiently. In git, files exist in one of two primary

states:

-

tracked: Files thatgitis actively monitoring. These can be further classified intounmodified,modified, andstaged. -

untracked: Files thatgithas not yet been instructed to track.

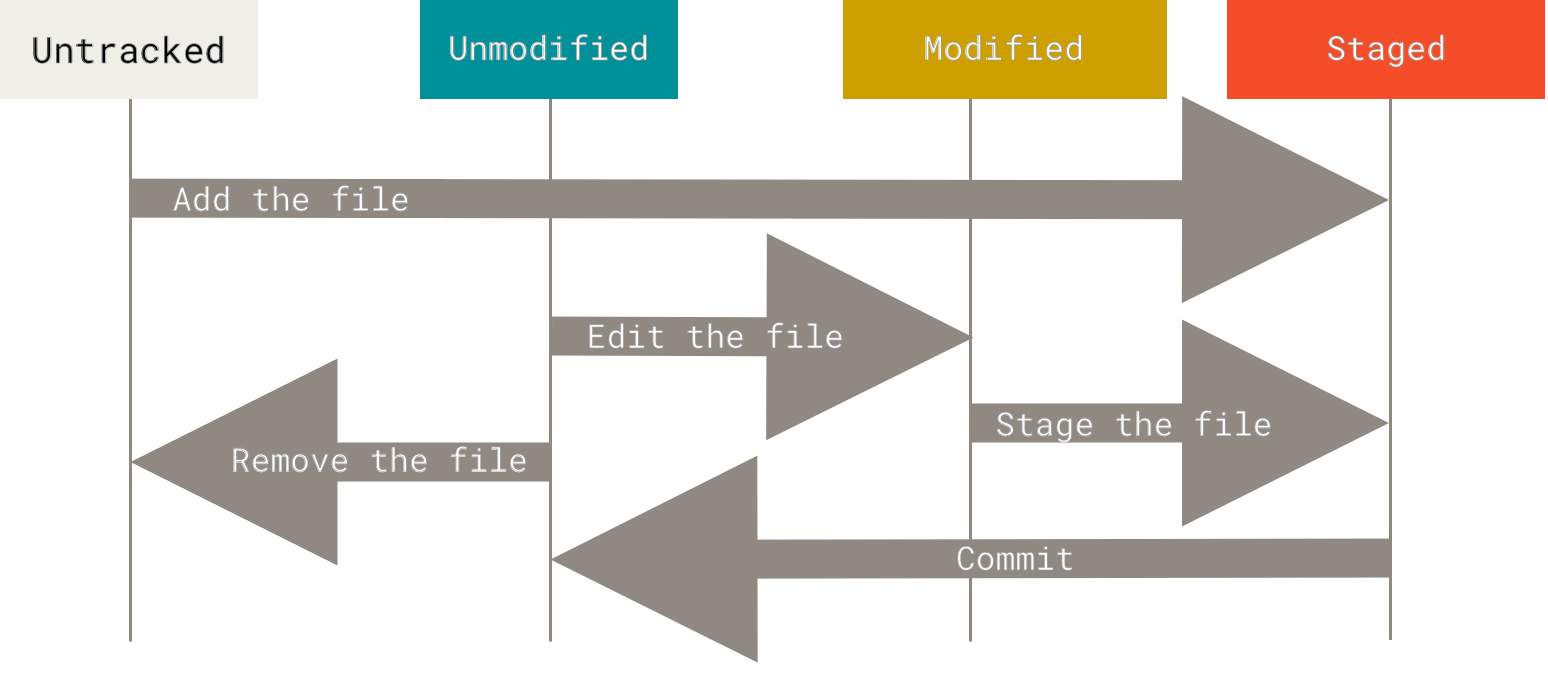

The following diagram from the official Git documentation illustrates how files transition between different states:

Checking File Status

To check the current status of files in a repo, use:

$ git status

This command will show which files are untracked,

modified, or staged. Keeping an eye on file

status is essential for managing changes efficiently.

For a deeper understanding of how git works, refer to the

official Git book. This

guide, however, focuses on getting you started quickly.

Tracking New Files

If we create a new file, such as README, inside a

repo:

$ touch README

At this point, the file is in an untracked state. To tell

git to start tracking it, run:

$ git add README

This moves the file to the staged state, meaning it is

ready for the next commit.

Committing Changes

Once a file is staged, we can commit it to the repo:

$ git commit

Executing this command opens the default editor, allowing

us to enter a commit message that describes the changes. This helps

keep a clear history of modifications. After committing, the file

moves to the unmodified state.

A standard commit workflow looks like this:

$ git add <file> # Stage changes

$ git commit # Commit changes

Simplifying the Commit Process

To streamline the process, we can use the following command to stage and commit all changes at once:

$ git add -A # Stage all changed files (equivalent to --all)

$ git commit -m "Brief description of changes" # Add commit message inline

With this, we have successfully completed the fundamental process of

recording changes in git, which is one of the most

frequently used operations in version control.

Step 4: Viewing History and Changes

As we start using git for version control, we will often

need to review past changes. The git status command

(introduced earlier) only displays the current state of the working

directory, but to view the complete modification history, we use:

$ git log

This command lists all commit records, including the

commit hash, author, date, and commit message. You might

notice that each commit has a unique hash value, which

serves as its identifier. If we ever need to revert to a specific

point in time, we can use this hash to do so.

Besides reviewing commit history, we may also need to

inspect the exact modifications made to files rather than just knowing

which files were changed. This is where the

git diff command becomes useful.

Viewing Unstaged Changes

To check modifications that have been made but not yet added to the staging area, use:

$ git diff

This command will display the specific changes, marking additions with

+ and deletions with -, making it easier to

identify modifications.

If you prefer to view changes word-by-word instead of by full lines, you can use:

$ git diff --word-diff

This highlights deletions as [-removed content-] and

additions as {+new content+}, providing a more detailed

comparison.

For even finer control over the diff format, you can use:

$ git diff --word-diff-regex=.

This treats each character as a separate comparison unit, which can be particularly useful for detecting changes in languages like Chinese, where a single character can be meaningful.

Viewing Staged Changes

If files have already been added to the staging area (git add), but have not yet been committed, we can inspect these changes

using:

$ git diff --staged

This works similarly to git diff, but specifically shows

the modifications that are currently staged for the next commit.

Comparing Two Commits

To compare the differences between two specific

commit points, we use:

$ git diff <commit-hash-1> <commit-hash-2>

This command highlights all modifications between the two commits, allowing us to track the evolution of the code over time.

These git diff commands are essential for version

management, helping us understand exactly what has changed and

ensuring smooth collaboration in a project.

Step 5: Reverting Changes

In addition to viewing history and inspecting modifications, we often

need to undo changes. Reverting a repo to a previous

commit is a common operation in git. We can

achieve this using the following command:

$ git reset <commit-hash>

This command adjusts the state of git, but it does not

necessarily affect the actual files. For example, if a file was

untracked before the specified commit, it will remain

untracked after the reset, meaning the file itself will

not be deleted but will instead be moved back to an

unstaged state.

--soft Option: Keep Changes

If we want to move back to a previous commit but keep all

modifications in the staged state, we can use:

$ git reset --soft <commit-hash>

This allows us to keep all changes ready for a new commit while removing the commit history beyond the specified commit.

--hard Option: Fully Restore to a Commit

If we want to completely discard all changes after a certain commit (including both staged and unstaged modifications), we can use:

$ git reset --hard <commit-hash>

This forces git to restore the repo to the

exact state of the specified commit, deleting all subsequent changes.

Since this operation is irreversible,

it should be used with caution to avoid losing

important work.

Choosing the right git reset mode depends on the

situation. If we want to undo a commit but keep our changes,

--soft is the best choice. If we are certain we need to

remove all changes beyond a specific commit,

--hard provides the cleanest reset.

Step 6: Managing Remote Repositories

In git, managing remote repositories (often

referred to as remote) is essential for collaboration and

code backup. We frequently need to push local changes to

a remote repository or pull updates from it to stay in

sync with teammates.

Connecting to an Existing Remote Repository

If we already have a remote repository, we first need to link it to

our local repo. We can do this using:

$ git remote add origin <URL> # "origin" is a commonly used alias for the remote repository

$ git remote -v # Verify remote repository links

Once linked, we can pull the latest version of the repository:

$ git pull origin master # "origin" is the remote name, "master" is the branch name

Some may wonder how this differs from git clone. The key

difference is that git clone simply copies a repository,

while git remote establishes a persistent connection

between the local and remote repositories, enabling synchronization.

Once local changes are made, they can be pushed to the remote repository:

$ git push origin master

Force Pull from a Remote Repository and Overwrite Local Changes

If our local repository conflicts with the remote version, we may need to forcefully update our local repository to match the remote repository. This can be done with the following commands (use with caution, as it will overwrite local changes):

$ git fetch --all

$ git reset --hard origin/master

$ git pull origin master

This ensures that our local repo is fully synced with the

remote version.

Pushing an Existing Local Repository to a Remote Repository

If we already have a local repo and want to upload it to

a newly created remote repository, we need to first add the remote

link:

$ git remote add origin <URL>

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

$ git push origin master

Since git push is a frequently used command, we can use

the -u parameter to set the default

remote and branch for future operations for

convenience:

$ git push -u origin master

After this setup, we only need to run:

$ git push

to push local changes, making the workflow much more efficient.

Conclusion

Congratulations! This article has now come to an end. We have covered

the fundamental usage of git, and I hope that after

reading this guide, you can quickly get started with version control.

However, the journey of learning git is far from over.

Even if you fully grasp everything discussed here, it is just the

first step.

Like many Unix-like tools, mastering

git requires continuous learning and hands-on practice to

truly understand its power and flexibility. If you want to explore

more advanced operations, be sure to check out my

"An Advanced Guide to Git: Practical Tips and Best

Practices".

Wishing you smooth sailing on your git learning journey!